Altamira Cave

Identification of the property

SubirAltamira Cave, Santillana del Mar, Cantabria

Access

From Castilla y León, take the A-67 motorway to Sierrapando. Then continue on the A-8/E-79 in the direction of Oviedo.

From Asturias and the Basque Country, take the A-8/E-70 motorway.

In both cases, in the town of Puente San Miguel, take Exit 234 towards Santillana del Mar on the CA-136. The road to Altamira Museum is signposted on the motorway and in Puente San Miguel and Santillana del Mar.

Geographic coordinates

UTM ETR89 30 N - X= 409,287.8m - Y= 4,803,273.8 m - Z= 152.37m

Description

Subir Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Topographic description

Altamira Cave is near the top of one of the hills surrounding the town of Santillana del Mar, within the boundaries of Altamira National Museum and Research Centre. It occupies a dominant position in the landscape, overlooking a wide territory. Its location must have been advantageous for the people who lived there in the Upper Palaeolithic, as the cave is two kilometres from the River Saja and five kilometres from the modern coastline, and within a short distance they would have been able to acquire a wide range of food resources as well as the firewood, river cobbles and other raw materials they needed for their subsistence.

The only entrance is situated 156m above sea level. This is a door that was opened up in about 1927, but during prehistory Altamira Cave would have had a large entrance where its occupants carried out their daily lives. However, this entrance collapsed about 13,000 years ago, burying the outer part of the archaeological deposit and blocking access to the cave until its discovery in the last third of the 19th century.

The cave is 290m long and is formed by a descending passage with smaller chambers on its side, which can be regarded as mere appendixes of the main passage. It varies between 50cm and 14m in height. In the case of the Chamber of the Polychromes, the roof where the paintings and engravings are situated is barely 7m beneath the surface.

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

The roofs and walls of the cave are formed by horizontal surfaces, forming trapezoidal cross-sections, owing to the generally horizontal pattern of the geological strata. The angular and stepped shape of the cave walls are caused by the collapse of large pieces of rock that have broken off and fallen to the floor in the course of millennia. In fact, its weak geological structure raised fears about the survival of the cave and thick walls were built inside the cave to stop a hypothetical collapse. Later, in the 1950s, the interior and exterior of the cave were altered again to allow the access of hundreds of thousands of visitors who came every year. Paths, steps and artificial structures to camouflage the lighting definitively changed the original appearance of the cave.

Therefore, the interior of the cave is very different from its morphology during prehistory. The changes in its form have also influenced the environmental conditions, such as the temperature, humidity and ventilation, of a natural setting in which the paintings had been preserved for millennia in a context of great natural stability.

Discovery of the paintings and the controversy about their antiquity

Altamira Cave was discovered by Modesto Cubillas, a local man, in 1868. Some years later he reported his find to Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, who can be considered its scientific discoverer, as he first saw the paintings in 1879.

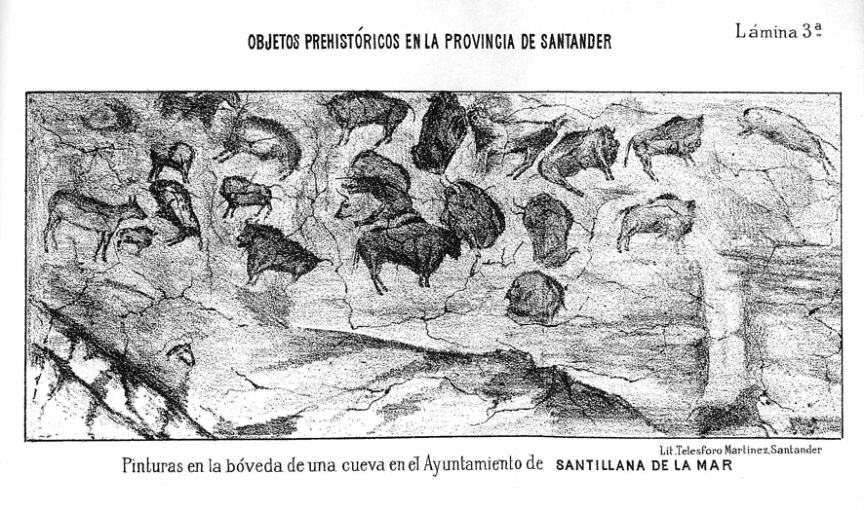

In 1880, Sautuola published his work inside the cave in a small book titled “Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander” (Brief Notes on some Prehistoric Objects in the Province of Santander). In this book he also described the discovery of the paintings, which he attributed, without a shadow of a doubt, to the Palaeolithic period.

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

General mistrust about the context of the discovery, the fresh appearance of the paintings and also the scientific postulates in vogue that excluded artistic skills from the abilities of the supposed ‘prehistoric man’ meant that the antiquity of the paintings in Altamira was not acknowledged until 1902, following the discovery of other caves with prehistoric art in the south of France. We can therefore think of Sautuola as ahead of his time, not only for Spanish science but for all European prehistory as his reasoning and logic, based on scientific knowledge, lay the foundations for the acknowledgement of the existence of art in the Upper Palaeolithic.

Archaeological research

Altamira Cave was used as a dwelling by Palaeolithic groups for at least 8000 years. However, it is possible that this occupation was much longer, perhaps from the start of the Upper Palaeolithic, but the boulders that cover the base of the stratigraphy stop further excavations to seek remains of older occupations now buried under those large rocks.

The human groups lived in a large area that extended over the whole of the entrance chamber of the cave, including a part that is now outside the entrance (and which was buried by the last great collapse), the interior of the first chamber and the Hall of the Polychromes.

The first excavations were carried out by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola in 1879 and 1880, when he dug the first soundings and unearthed flint artefacts, spear points, needles, beads, and remains of animals and shells, as well as a large amount of colouring matter that, he stated, “may have been used to make these paintings”. The objects he found enabled him to establish the age of the remains, while the paintings would be of the same age, also dated in the Palaeolithic (Sanz de Sautuola, 1880). This affirmation only brought him the incomprehension of many of his colleagues.

The next excavations were undertaken by H. Alcalde del Río from 1903 to 1905, and were followed by the excavations of H. Obermaier in 1924 and 1925, and González Echegaray and Freeman in 1980 and 1981. From Alcalde del Río’s fieldwork, a stratigraphic sequence was established, and it was maintained for 100 years without any variations. According to this sequence, the Solutrean period was followed by the Lower Magdalenian without any apparent break, owing to the difficulty in clearly determining the separation between the two levels.

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

In 2004, Altamira Museum designed a research project that did not envisage a true excavation but a new reappraisal of the stratigraphic sections that already existed, their study and systematic sampling to obtain palaeoclimate information and sequential absolute dates for each of the layers that could be differentiated in the stratigraphy. This work succeeded in identifying three occupation periods, instead of two, and defined a chronocultural and climate sequence in great detail. At the base of the sequence, an archaeological level unknown until then was dated in the Upper Gravettian period, in about 22,000 BP. Above this, a thick stratum covered from the early Solutrean to the transition to the Lower Magdalenian, between 19,630 and 17,200 BP. Finally, in the upper part of the stratigraphic sequence, another layer corresponded to the Lower Magdalenian and the transition to the Middle Magdalenian, between 15,600 and 14,070 BP.

Prehistoric art in Altamira Cave

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

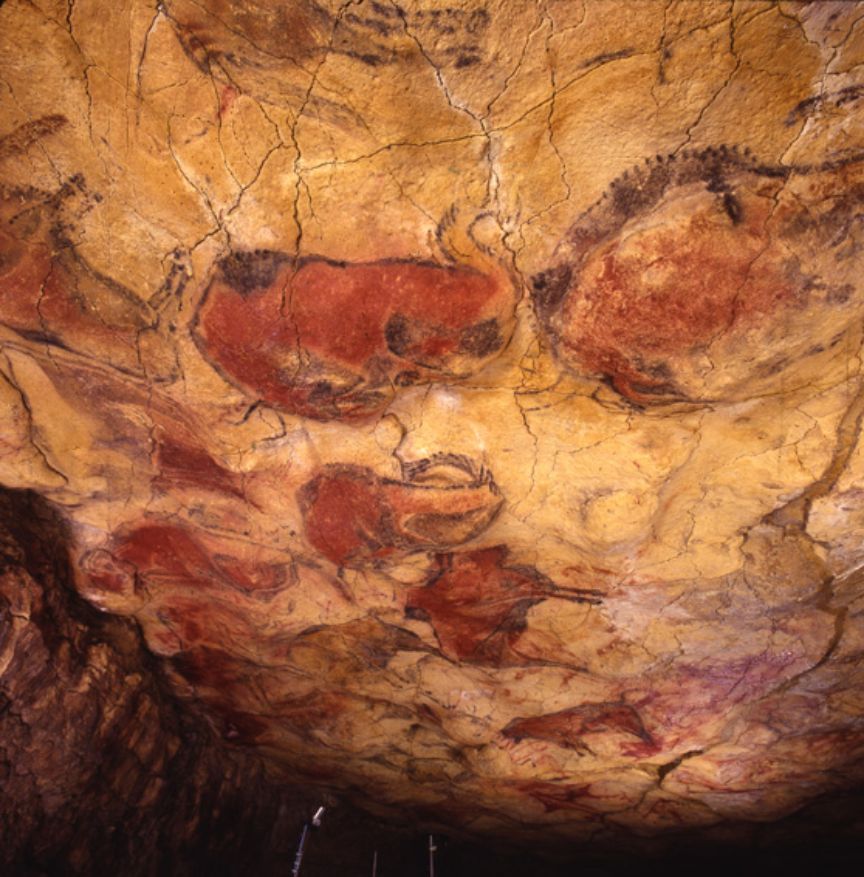

Upper Palaeolithic cave art was produced by hunter-gatherers and appears very homogeneously across much of Europe. Altamira Cave is one of the great sites with this form of art; it is outstanding because of the polychrome paintings and the naturalism of the figures, and also as it is a good example and display of the artistic themes and techniques employed over several millennia.

The animals represented in Altamira are common to Palaeolithic art in northern Spain, although bison are the defining and distinctive element of the cave. The polychrome bison are located on the roof of a chamber that, as mentioned before, was the continuation of the large entrance area. The artists who painted those figures must have been near people who were cooking, working or playing inside the entrance. In other words, the Hall of the Polychromes was not a symbolic place because it was distant and concealed but because of its semantic meaning and codified iconography.

Red deer stags and hinds, horses and to a lesser extent, ibex complete the figurative repertory. They are distributed throughout the cave, painted and engraved with different artistic techniques and of different ages.

Other representations are non-figurative or abstract. These are the so-called ‘signs’ whose meaning is unknown but which evidently formed a system of communication that Palaeolithic people were able to understand. In Altamira there are some engraved signs in the form of ‘huts’ or ‘comets’ on the right hand side of the Hall of the Polychromes. Other black rectangular signs, filled with diverse patterns are found in the final passage; other large red ladder-shaped signs (over 2.25m long) are located in a narrow side passage; while signs known as ‘claviforms’ are painted on the roof in the Hall of the Polychromes.

Human representations are not common in Palaeolithic art, but some of the most characteristic types of figures, known as ‘anthropomorphs’, are represented in Altamira. These are fantastic depictions that combine more or less clear human traits (raised arms, sometimes showing the fingers, and sometimes representing the phallus) but their outline, always in profile, is indeterminate. Some of these figures appear on the roof in the Hall of the Polychromes. Other figures that display human features are the ‘masks’ in the final passage at Altamira. These consist of angular shapes in the wall, to which small black marks have been added to represent eyebrows, eyes, a moustache and fangs, creating ghost-like images that shroud this narrow passage in mystery.

The age of cave art can be determined by different dating methods. Thus, paintings drawn with charcoal can be dated by carbon 14. This has shown that the famous polychrome bison were painted about 14,500 years ago. However, depictions that do not contain organic matter in their pigment cannot be dated with this method. Until a few years ago, figures painted in red (and therefore without organic matter in their composition) could not be dated but the development of an old dating method, using Uranium/Thorium, now allows the age of small amounts of calcium carbonate to be determined. This method can be applied to cave art as it requires very small samples of a few cubic millimetres to be able to date the calcite that has grown above or underlies an artistic representation. Using this system, it is now known that a sign painted on the roof in the Hall of the Polychromes is at least 35,000 years old, much older than was previously suspected.

Altamira Cave is decorated with Palaeolithic art throughout its whole length, from the Hall of the Polychromes to the final passage. In this way, the hall known as ‘La Hoya’, a small chamber on a lower level of the cave, contains some black paintings, such as a bison, a female deer and several ibex, that form a very homogeneous group in terms of their style and artistic technique, which suggests that they were all painted at the same time. The final passage is a corridor nearly 100m long that becomes narrower and lower towards the end. It holds a large number of different kinds of figures in different styles and techniques; this shows that this narrow corridor was visited during millennia to produce those figures.

Bibliography

SubirALCALDE DEL RÍO, H. 1906. Las pinturas y grabados de las cavernas prehistóricas de la Provincia de Santander: Altamira - Covalanas - Hornos de la Peña - Castillo. Santander: Impr. Blanchard y Arce. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:bd5bb5d1-4077-47f8-9626-62564ca12a31/alcalde-del-rio-1906-las-pinturas-y-grabados2.pdf

HERAS, C. de las, LASHERAS, J.A., MONTES, R., RASINES, P., y FATÁS, P. 2008. Nuevas dataciones de la Cueva de Altamira y su implicación en la cronología de su arte rupestre paleolítico. Cuadernos de arte rupestre. Revista del Centro de Arte Rupestre Casa de Cristo de Moratalla Murcia, 4. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:0b74b00d-17c7-4841-a955-e8680c043c07/vvaa-2008-nuevas-dataciones-altamira.pdf

HERAS, C. de las, MONTES, R., y LASHERAS, J.A. 2013. Altamira: nivel gravetiense y cronología de su arte rupestre. En: HERAS, C de las, LASHERAS, J.A., ARRIZABALAGA, Á., y RASILLA, M. (eds.). Pensando el Gravetiense: nuevos datos para la región cantábrica en su contexto peninsular y pirenaico. Monografías del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, no. 23: 476-491. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:865b0772-0490-40bc-a49f-01fcc5117876/heras-montes-lasheras-2013-nivel-gravetiense.pdf

HERAS, C. de las, y LASHERAS, J.A. 2014. La cueva de Altamira. En: SALAS, R. (ed.) Los cazadores y recolectores del Pleistoceno y del Holoceno en Iberia y el estrecho de Gibraltar: 615-627. Burgos: Universidad de Burgos y Fundación Atapuerca. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:bae55b0d-adf5-4953-a57c-fabf315038db/heras-lasheras-2014-cueva-altamira.pdf

LASHERAS, J.A. 2002. El Arte Paleolítico de Altamira. En: LASHERAS, J.A. (ed.). Redescubrir Altamira: 65-92. Madrid: Turner. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:44b42def-1765-4824-a041-27b27a4b7b5d/lasheras-2002-arte-paleolitico-altamira.pdf

LASHERAS, J.A., y HERAS, C. de las. 2004. Estudio introductorio [texto traducido a inglés, francés y portugués] a SANZ DE SAUTUOLA, M. 1880. Breves Apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander. BOTÍN, E. (prol.). Madrid: Grupo Santander. 2 vol. 204 p. + 27 p. Edición no venal. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:838c6f98-14e1-4a62-bd30-2e7c1f5b081b/altamira-fac-espanol.pdf

LASHERAS, J. A., MONTES, R., MUÑOZ, E., RASINES, P., HERAS, C. de las, y FATÁS, P. 2005/ 06. El proyecto científico Los Tiempos de Altamira: primeros resultados. En: Homenaje a Jesús Altuna, tomo III: Arte, Antropología y Patrimonio arqueológico. Munibe Antropologia – Arkeologia 57: 143-159. San Sebastián: Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:8b3ae40f-f8d8-4ff2-8cb0-c82e4f51b685/vvaa-2005-2006-homenaje-altuna.pdf

PIKE, A. W. G., HOFFMANN, D. L., GARCÍA-DIEZ, M., PETTITT, P.B., ALCOLEA, J., BALBÍN, R. D., GONZÁLEZ-SAINZ, C., HERAS, C. de las, LASHERAS, J. A., MONTES, R., y ZILHAO, J. 2012. U-Series dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 caves in Spain. Science 336-6087: 1409-1413.

SANZ DE SAUTUOLA, M. 1880. Breves Apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander. Santander: Imp. y Lit. de Telesforo Martínez. http://www.cultura.gob.es/mnaltamira/dam/jcr:0f73820d-b6ed-4388-bf7f-4599a544898b/breves-apuntes-original.pdf