El Castillo Cave

Identification of the Property

SubirMonte Castillo, Puente Viesgo, Autonomous Community of Cantabria

Access

From the N-623 road, turn off in the centre of the town of Puente Viesgo, go past the car park and take the road up the hill to Monte Castillo. This ends at the car park for visitors; from there walk up to reception and the interpretation centre, located outside the cave entrance.

Geographical coordinates

UTM 30T 421800E / 4793925N Z: 190

Descripción

SubirTopographic description

Monte Castillo is a conical limestone hill, forming the easternmost spur of Sierra del Escudo de Cabuérniga, a feature separating the coastal lowlands from the interior valleys in the west of Cantabria. It stands over the left bank of the River Pas, dominating a wide fluvial plain at the start of the “lower Pas Valley” and also the natural route from this valley to Besaya valley. The cave consists of a large vestibule and an interior part. The rock overhanging the entrance collapsed on several occasions during the Pleistocene, and the fall of boulders affected the archaeological occupation, restricting the available area to the rear of the vestibule in more recent periods. The interior of the cave begins in the “Great Hall”, whose central part is filled with enormous collapsed blocks. From here a passage leads off towards the north-east, with other side-passages. The form of the “Great Hall”, with numerous fragmented areas, fissures and small passages, plays an important part in the distribution of the prehistoric art. The total length of the cave is 759m and the maximum depth reached below the entrance is -16m.

Date of Discovery

The archaeological deposit and art inside the cave were discovered by H. Alcalde del Río in 1903.

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Archaeological research

After the cave had been explored by Alcalde del Río, an intensive programme of excavations was carried out between 1910 and 1914. This was funded by the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine and directed by H. Breuil and H. Obermaier. A depth of -18m was reached in the vestibule, in the course of documenting one of the most important Palaeolithic deposits in Europe, with a long sequence including levels of Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, Azilian, Mesolithic and recent Prehistory. However this great stratigraphic sequence was not published at that time, apart from a few brief items in L’Anthropologie. Many years later, in the 1970s, the archaeological documentation generated by the excavations was studied by Victoria Cabrera Valdés, who published the first great monograph on the deposit. The same prehistorian restarted excavations at the site in the 1980s, and continued this work until her death in 2004. Other 55 contributions to the understanding of the archaeological record at El Castillo, particularly its more recent phases, have been made by J. González Echegaray (1951) and R. Ontañón Peredo (2000).

Regarding the prehistoric art, El Castillo Cave was included in Alcalde del Río’s study of the decorated caves in the province of Santander (1906) and was later analysed in the major work Les Cavernes de la Région Cantabrique, published by Alcalde del Río, H. Breuil and L. Sierra (1911). In the 1930s, the Commission of Palaeontological and Prehistoric Research dedicated several seasons’ fieldwork to the study and reproduction of the paintings and engravings in the cave, under the direction of Count de la Vega del Sella and with F. Benítez Mellado in charge of producing the tracings and copies. Since 2004, a team directed by Marc Groenen has been revising the rock art in the cave.

Artistic contents; paintings and engravings:

The art in El Castillo Cave is distributed throughout practically the whole cave, and forms one of the most important ensembles of Palaeolithic art in the world. Here we can only summarise the contents, by describing the more important figures, and omitting many others, particularly the less spectacular although equally significant engravings. Within the cave, the art appears to be concentrated in certain groups. However, it must be pointed out that the inventory of depictions is growing in the course of the new research being undertaken.

A lower passage, below the door leading from the vestibule to the Great Hall, has a group of figures engraved with single lines, representing horses, stags, hinds and ibex.

Their style and technique correspond to archaic art. The Great Hall is decorated on almost all its walls, including a final side-passage. However, many of the paintings, in red and black, are badly faded. They represented a stag, auroch and a group of horses.

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

Pulse para ampliar

This chamber also has a large number of engravings, above all of hinds, sometimes with magnificent striated heads and chests. These drawings are significant because they are identical to figures depicted on scapulae discovered within the early Magdalenian layer in the vestibule, dated to between 16,500 and 14,000 B.P. Leaving the Great Hall on the right, a series of paintings includes a large bison, head facing downwards; only the fore-quarters were outlined in red and the natural shape of the rock completes the body. A large horse is similarly reproduced in red.

A little further down, the wall has superimposed figures. The most recent paintings are bichrome bison, very similar in their technique and appearance to the bison on the ceiling at Altamira. They are outlined in black and engraved, and in fact much of the red colour inside their bodies comes from earlier paintings of hinds, superimposed on even earlier stencilled images of hands. Radiocarbon dating has shown that the bison were produced on at least two different occasions, about 13,500 and 13,000 B.P.

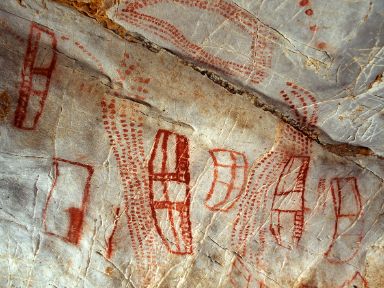

At the base of this wall, the entry of a side passage on the right has a large number of stencilled hands, mostly left hands, on the ceiling and wall. These may be the oldest paintings in the cave, and superimposed on some of them are at least seven bison with a very simple outlined form in yellow. Red abstract signs and animal engravings complete this group. A chamber to the side of this passage has a notable group of red quadrilateral signs. There are ten of these, characteristically divided into three areas, with a border filled with short lines. They are associated with parallel lines of similarly red dots.

As the passage continues, it has a horse in red, with log ears bent forwards and arrows in its flank. 56 The Second Chamber, which also can be reached directly from the Great Hall, has the figure of a bison on a large stalagmite; it is shown vertically, head upwards, and was produced by sculpting, engraving and painting the side of the stalagmite. The same area of the cave has a large red quadrilateral sign, and an interesting group of bell-shaped signs in red, with a superimposed branching sign in black. The following chambers have small groups of animal paintings, particularly two bison outlined in black. A side-passage on the left has a face or “mask”, where an eye and a nose were added to a suggestively-shaped rock pedant.

The long final corridor begins with the head of an auroch in red, with one ear and its horns in twisted perspective. It is followed by over a hundred red discs, produced by spraying the pigment on the wall, and arranged in a long series along the right hand wall. The painting of a possible mammoth is found at the end of this passage. It is also interesting that the Great Hall contains a small number of schematic human figures, attributed to the Post-Palaeolithic period. The decoration of El Castillo clearly took place over a very long period of time, from the Gravettian to at least the middle Magdalenian.

The oldest art is probably the red sprayed paintings; the disc and stencilled hands, whereas the most recent figures include a few engravings superimposed on a “bichrome” bison. The distribution of the motifs is interesting as the oldest depictions are found in the entire cave, including the parts nearest the end. In contrast, paintings and engravings of a more clearly Magdalenian style are most common in the central parts of the cave or nearer the entrance.

Bibliography

SubirALCALDE DEL RÍO, H., BREUIL, H., SIERRA, L. 1911. Les Cavernes de la Région Cantabrique (Espagne). Monaco: Impr. Veuve A. Chêne.

BREUIL, H., OBERMAIER, H. 1913. Fouilles de la Grotte du Castillo (Espagne). XIV Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistorique (Génève) I: 361-362.

BREUIL, H., OBERMAIER, H. 1914. Travaux en Espagne. Fouilles du Castillo à Puente Viesgo (Santander). (Rapports sur les travaux de l´année 1913). L'Anthropologie XXV: 233-234.

CABRERA, VALDÉS 1984. El yacimiento de la Cueva de El Castillo (Puente Viesgo, Santander). Madrid: Bibliotheca Praehistorica Hispana XXII.

CABRERA, VALDÉS 1993. Pasado y presente en la investigación del yacimiento de la Cueva del Castillo. Puente Viesgo, Cantabria. En MANGAS MANJARRÉS, J. y ALVAR EZQUERRA, J. (eds.): Homenaje a José Mª Blázquez I: 243-251. Madrid: Ed. Clásicas.

CABRERA VALDÉS, V., BISCHOFF, J. 1989. Accelerator 14C Dates for Early Upper Palaeolithic (Basal Aurignacian) at El Castillo Cave (Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science 16: 577-584.

CABRERA VALDÉS, V., LLORET MARTÍNEZ DE LA RIVA, M., BERNALDO DE QUIRÓS, F. 1996. Materias primas y formas líticas del Auriñaciense Arcaico de la Cueva del Castillo, Puente Viesgo, Cantabria. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie I, 9: 141-158.

CABRERA VALDÉS, V., PIKE-TAY, A., BERNALDO DE QUIRÓS, F. 2000. The beginnings of the Upper Palaeolithic in Cantabria (Spain): levels 18B and 18C of the Cueva del Castillo. Journal of Human Evolution 38, 3.

CABRERA VALDÉS, V., BERNALDO DE QUIRÓS, F. 2000. Excavaciones arqueológicas en la cueva de El Castillo (Puente Viesgo). En R. Ontañón (coord.): Actuaciones Arqueológicas en Cantabria 1984-1999: 23-34. Santander: Consejería de Cultura y Deporte del Gobierno de Cantabria.

GARRALDA BENAJES, M. D., TILLIER, A. M., VANDERMEERSCH, B., CABRERA VALDÉS, V., GAMBIER, D. 1992. Restes humains de l’Aurignacien archaique de la Cueva de El Castillo, Santander, Espagne. L’Anthropologie XXX/2: 159-164.

MOURE ROMANILLO, A., GONZÁLEZ SAINZ, C., BERNALDO DE QUIRÓS, F., CABRERA VALDÉS, V. 1996. Dataciones absolutas de pigmentos en cuevas cantábricas: Altamira, El Castillo, Chimeneas y Las Monedas. En A. Moure Romanillo (ed.): “El hombre fósil” 80 años después: 295-324. Santander: Universidad de Cantabria, Fundación Marcelino Botín, Institute for Prehistoric Investigations.

VALLADAS, H., CACHIER, H., MAURICE, P., BERNALDO DE QUIRÓS, F., CABRERA VALDÉS, V., UZQUIANO, P., ARNOLD, M. 1992. Direct radiocarbon dates for prehistoric paintings at the Altamira, El Castillo and Niaux caves. Nature 357, pp.68-70.

ONTAÑÓN PEREDO, R. 2000. Prehistoria reciente en la cueva del Castillo (Puente Viesgo, Cantabria). Sautuola VI (1999): 229-241 (R. Bohigas Roldán y C. Fernández Ibáñez (coord.) Estudios en Homenaje al profesor Dr. García Guinea. Santander: Gobierno de Cantabria. Consejería de Cultura y Deporte).

ONTAÑÓN PEREDO, R. 2018. 10 Cuevas Patrimonio Mundial en Cantabria. Santander: Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deporte - Gobierno de Cantabria / Asociación de Amigos del MUPAC.